Monday, 17 June 2013

NFDP13: Plenary Panel Two: Where do we want to go?

This is my final post about the Now and Future of Data Publishing symposium and is a write-up of my speaking notes from the last plenary panel of the day.

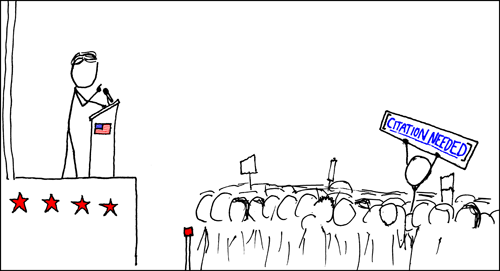

As before, I didn't have any slides, but used the above xkcd picture as a backdrop, because I thought it summed things up nicely!

My topic was: "Data and society - how can we ensure future political discussions are evidence led?"

"I work for the British Atmospheric Data Centre, and we happen to be one of the data nodes hosting the data from the 5th Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5). What this means is that we're hosting and managing about 2 Petabytes worth of climate model output, which will feed into the next Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's Assessment Report and will be used national and local governments to set policy given future projections of climate change.

But if we attempted to show politicians the raw data from these model runs, they'd probably need to go and have a quiet lie down in a darkened room somewhere. The raw data is just too much and too complicated, for anyone other than the experts. That's why we need to provide tools and services. But we also need to keep the raw data so the outputs of those tools and services can be verified.

Communication is difficult. It's hard enough to cross scientific domains, let alone the scientist/non-scientist divide. A repositories, we collect metadata bout the datasets in our archives, but this metadata is often far to specific and specialised for a member of the general public or a science journalist to understand. Data papers allow users to read the story of the dataset and find out details of how and why it was made, while putting it into context. And data papers are a lot easier for humans to read that an xml catalogue page.

Data publication can help us with transparency and trust. Politicians can't be scientific experts - they need to be political experts. So they need to rely on advisors who are scientists or science journalists for that advice - and preferably more than one advisor.

Making researchers' data open means that it can be checked by others. Publishing data (in to formal data journal sense) means that it'll be peer-reviewed, which (in theory at least) will cut down on fraud. It's harder to fake a dataset than a graph - I know this personally, because I spent my PhD trying to simulate radar measurements of rain fields, with limited success!)

With data publishing, researchers can publish negative results. The dataset is what it is and can be published even if it doesn't support a hypothesis - helpful when it comes to avoiding going down the wrong research track.

As for what we, personally can do? I'd say: lead by example. If you're a researcher, be open with your data (if you can. Not all data should be open, for very good reason, for example if it's health data and personal details are involved). If you're and editor, reviewer, or funder, simply ask the question: "where's the data?"

And everyone: pick on your MP. Query the statistics reported by them (and the press), ask for evidence. Remember, the Freedom of Information Act is your friend.

And never forget, 87.3% of statistics are made up on the spot!"

_________________________________________________________

Addendum:

After a question from the audience, I did need to make clear that when you're pestering people about where their data is, be nice about it! Don't buttonhole people at parties or back them into corners. Instead of yelling "where's your data?!?" ask questions like: "Your work sounds really interesting. I'd love to know more, do you make your data available anywhere?" "Did you hear about this new data publication thing? Yeah, it means you can publish your data in a trusted repository and get a paper out of it to show the promotion committee." Things like that.

If you're talking the talk, don't forget to walk the walk.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment